Evidence of coal mining around Boothstown dates to the 14th century, and leases for coal extraction are evident from around 1500. During the 17th century, extraction of coal was primarily from shallow, or open-cast mines, known as Bell Pits, though techniques for deeper mining continued to be developed. The chief hazards to be overcome were gases (necessitating improved ventilation) and water. From 1729 a drainage sough was constructed from Walkden to Worsley; it was originally 1,100 yards long, of which 600 yards were underground, and was later extended.

Increasing demand for coal from the growing city of Manchester required more efficient means of production and transportation. In response, Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, the famous Canal Duke, commissioned the building of the Bridgewater Canal from Booth’s Bank to Worsley, and on to Manchester. The Canal Act was passed in 1759, and the canal into Manchester was operational by 1765. It is regarded as an 18th century masterpiece, and was engineered first by John Gilbert, then by James Brindley.

By 1776 the Bridgewater Canal was extended to the River Mersey at Runcorn, thus linking Manchester with Liverpool by waterway, and in 1795 an Act was passed allowing the canal to be extended westwards to Leigh.

The construction of an underground canal, or navigable level, was also begun in 1759. The entrance to the level was by the Bridgewater Canal in Worsley village, and the tunnel extended north towards Walkden, with further tunnels along the coal seams being constructed at right angles to the main level. New pits were sunk to meet the navigable level, which enabled coal to be mined and carried underground by boat to the main canal. In addition, the level provided a means of drainage, and a source of water for the Bridgewater Canal. Further local coal rights were acquired by the Duke of Bridgewater beyond his own estate, such as those agreed with Mr. Clowes of Booth’s Hall in 1789.

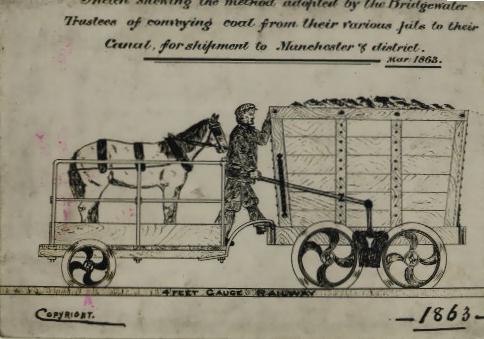

The coal seam running from Boothstown to Worsley is called the Four Feet Seam, and it was exploited because of its proximity to the canal. For example, the pit at Abbot’s Fold was linked to the canal by horse-tramway by 1764. The tramway extended one and a quarter miles from Hilton Lane, crossing Newearth Road at Mather Fold and running south to the canal at Boothstown. In the 1840s it was extended to serve the Ellenbrook pits.

The picture below, from 1863, shows the means by which the wagons operated. The tramway was gravity driven; the full wagons, with a horse and brakesman on board, rolled down to the canal; after unloading, the empty wagon was pulled by the horse back up to the pit. It crossed Newearth Road at Ellenbrook where, from 1862, a manually operated traffic-light used red and white lamps to tell pedestrians and horse-drawn traffic whether the level crossing was clear – it was the pedestrian and horse traffic which had to stop as the trams rumbled on. Was this the first traffic-light in the world?

The engineering feat of constructing fifty miles of underground canals from Worsley was also undertaken in Boothstown with the construction of the Chaddock Level. It extended over 6,000 yards from the Bridgewater Canal, south of Boothstown, to the Chaddock colliery, and beyond to the Queen Anne pit (which operated from 1810 to 1820) and the Henfold pit. The Chaddock Level was used to transport coal during the 19th century, and though precise dates of construction and disuse are unknown, the keystone on the entrance is dated 1816.

After 1841 women, and children under 12, were no longer required to work underground in Worsley pits. Women still worked above ground, however, and the picture below shows women from a local pit head (Gibfield in Atherton) in 1905.

The 1848 map of Boothstown suggests that Chaddock Colliery was the main pit, with the entrance to the Chaddock Level shown on the canal. Other coal pits are shown at Abbot’s Farm and Mosley Common, originally called Stonehouse Pits. The Abbot’s Fold and Chaddock (closed 1868) pits have disappeared on the 1894 map, by which time the Mosley Common colliery, with deep pits sunk in the 1860s, covered a much larger area, and had its own railway link to the canal.

In 1864 an LNWR main railway line was built from Worsley to Wigan and it became a means of distributing local coal. The tramways were replaced by standard gauge steam railways which connected the LNWR mainline and the canal, where the basin at Booth’s Bank was constructed for unloading coal. The use of the main navigable level for transporting coal thus ended in 1887, though it continued to provide a drainage function.

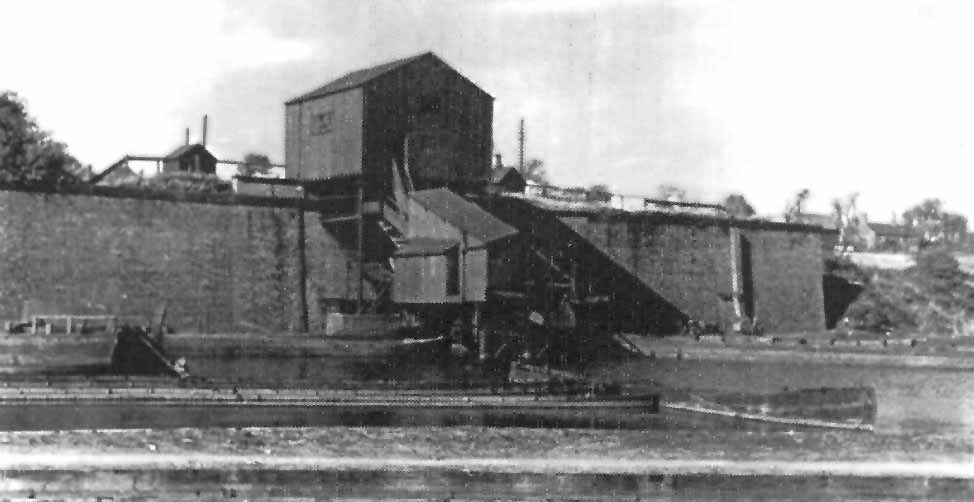

The picture below, possibly from the 1950s, shows the coal wharf at the Boothstown canal basin where coal from the mineral railway was loaded onto the canal boats. The canal was also used for other commercial traffic, including clay from local pits.

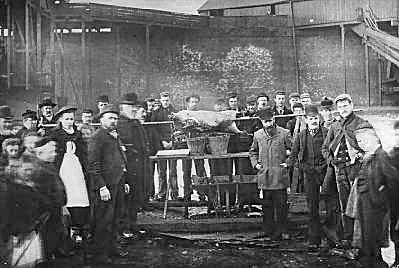

Pictured below are workers at the Boothstown canal basin in 1895 roasting a lamb given to them by Mr. Simpson, the village butcher, when the canal froze over and made work impossible; Mr. Simpson is standing with his hands in his jacket pockets, to the right of the roast.

In 1921, the 4th Earl of Ellesmere founded the Bridgewater Collieries and Bridgewater Wharves companies, separating these interests from his main estate to protect against death duties, taxation and possible fragmentation of the estate arising from any future nationalisation of the mines. (The mines had been government-managed from the 1914-1918 war until they were returned to mine owners in 1921.) In 1923, the Collieries and Wharves were sold with the estate to the new Bridgewater Estates Ltd, of which they became subsidiary companies. In 1924 the first local subsidence problem occurred when the collapse of a mine shaft damaged a house in Boothstown. Following several years of recession and poor industrial relations, a group of local mining companies, including Bridgewater Collieries and Wharves, merged to form Manchester Collieries Ltd in 1929, and Bridgewater Estates Ltd gave up its shareholding in its two former subsidiaries.

Mosley Common colliery employed over 2,000 by 1919, and became part of the Manchester Collieries company in 1929, before the takeover by the National Coal Board in 1947. The picture below shows Mosley Common colliery at its peak in 1956; St. Mary’s Church, Ellenbrook can be seen at the bottom of the picture.

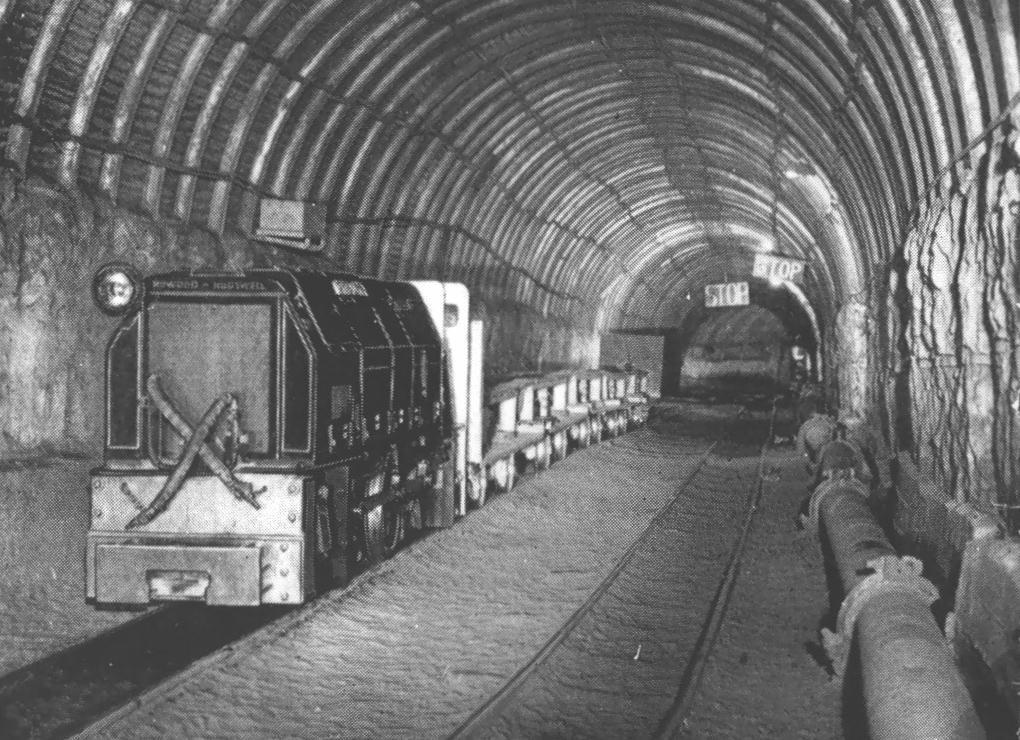

The picture below shows a locomotive underground at Mosley Common, at around the same time. By the late 1950s, the colliery employed 3,000, and was among the largest and most modern pits in the country. However, it was closed in 1968 without having been exhausted, and the site was cleared by 1974. (Also in 1968, Yates’s textile mill, which had dominated the village centre since 1874, was closed down. It was not demolished until the 1980s, prior to housing being built on the site either side of the culverted Stirrup Brook.)

Pictured below is the Duke of Edinburgh on a visit to Mosley Common Colliery in 1952. The visit was shown on a newsreel film at the time. The Duke went underground.

The picture below shows a train on the mineral railway on the level crossing near Vicar’s Hall Bridge in 1963. Some half a million tons of coal were still carried annually on the canal in the late 1950s, serving the power station and industry in Trafford Park. But the last coal was carried in 1970, and commercial traffic ended in 1974. With the closure of the remainder of the pits in the Lancashire coalfield, the Mines Rescue Station, built in 1933 on Ellenbrook Road, was closed in the 1990s, and the distinctive yellow rescue vehicles were no longer to be seen. The building has now been converted to residential use.

After the Coal Industry

Following the closure of the mines, much of the route of the railway from Mosley Common to the canal was built on for housing during the 1970s. The area south of the village became a source of fascinating industrial archaeology through the 1970s and 1980s, after mining had ceased, and before redevelopment in the 1990s. The fields and scrubland between the village and the canal were criss-crossed with the paths of disused railways; old sleepers and buffers peeped through the weeds (see below), and the basin became neglected as the grave of sunken coal boats.

The two pictures below show the basin in 1989 before development. Abandoned coal boats lie half-sunken, and the words National Coal Board can be read on the bows.

The picture below shows work on the drainage and dredging of the basin in 1992. In all, thirty-seven boats were discovered to be lying four-deep, and were not preserved. Following redevelopment, the basin is now a marina overlooked by new housing, with a focal point in the Moorings pub.

Astley Green Colliery, which opened in 1908, reached its peak in the 1950s when its two shafts and fourteen underground levels employed almost 2,300 people. The site, now disused, is the only preserved pit head in Lancashire, and is operated by the Red Rose Steam Society. The steam winding engine, built by Yates and Thom of Blackburn in 1912, was the largest engine ever used in the Lancashire coalfield, and is believed to be the largest steam winding engine left in Europe.

Acknowledgements

This web page was written by Tony Smith. The story of the Bridgewater collieries and canal is told in The Duke of Bridgewater’s Canal by Frank Mullineux (Eccles and District History Society, 1988), The Bridgewater Heritage by Christopher Grayling, Bridgewater Estates plc, 1983, and in The Canal Duke’s Collieries: Worsley 1760-1900 by Glen Atkinson (published by Neil Richardson, Radcliffe). Additional material was obtained from a local history information pack, provided by Walkden Library, and produced by local historians A. Monaghan, C.E. Mullineux and C.Woodward, and from Boothstown: A Chronological History by Carol Woodward, published by City of Salford Libraries and Information Service, Arts and Leisure Department, 1994; the booklet includes a bibliography of historical sources. K.R. Hardman’s pamphlet Chaddock Colliery (Engine Row) and Boothstown’s Own Navigable Level, was published by the City of Salford Arts and Leisure Department in 1994. Notes on the Astley Green steam engine from the guide to the heritage trail In Brindley’s Footsteps. Colour photographs are copyright (c) Tony Smith. The photograph of the roast at the basin was supplied by C.E. Mullineux; other black and white photographs were kindly supplied by Walkden Library (except picture of the Duke of Edinburgh at Mosley Common Pit – source and copyright unknown).