The Windmill in Boothstown

The site of the Boothstown windmill (referred to in the description of the Victorian ramblers) can still be seen. The mound is behind the former Conservative Club in Boothstown, in front of Mill Street. (In the last couple of years new housing has been built on the site and the Conservative Club is now called the Windmill Club.) This mill was built by Thomas Smith in the mid-18th century for grinding corn; it lasted more than 100 years until it was demolished in 1874 by a Mr. Thomas Silcock, who then owned the property.

It is said that some years ago, an excavation of the site took place by people who thought that it might be a burial mound; what they found, however, were the foundations of the windmill.

Two historical references to corn milling in Boothstown have been found. John Buckley’s History of Tyldesley (published in 1878) relates how a miller was found guilty of stealing flour and was sentenced to be tied to a cart and flogged. Another miller was brought by the constables to Worsley Manorial Court Leet in the mid-19th century and fined by the jurors for “running a hare in the Manor of Worsley” – that is, poaching.

A Windpump in Boothstown

In a field just north of the Bridgewater Canal, and on the east side of Vicar’s Hall Lane, there once stood another windmill. Clearly shown on the Ordnance Survey map of 1894, it had an unglamorous purpose. It was a windpump used in the functioning of the Boothstown sewage farm, where sewage was spread on the land to be disposed of organically. In September 1893 Tomlinson & Son of Patricroft repaired this windmill, described as used in purifying the sewage matter. By November it was reported to the Worsley Council that it had been reconstructed, and was in good order, “it is doing remarkably well and there is a great improvement in water through”.

Seven Cotton Mills in (and around) Boothstown

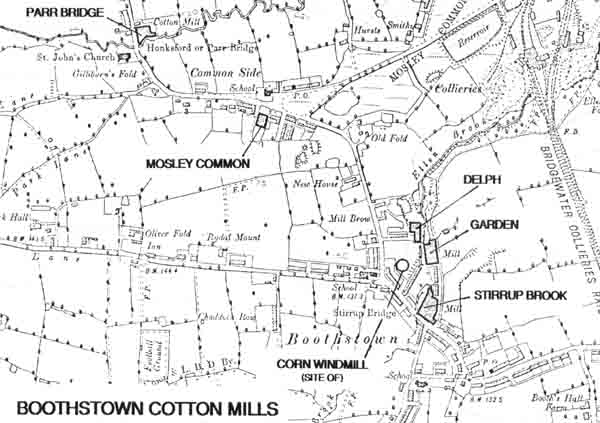

In a period of just over 200 years, Boothstown had a succession of seven cotton mills on five different sites, four of them originated by the Smith family who had the windmill.

Hampsons Delph Mills (three mills in the Delph west of the brook)

Thomas Smith was a corn dealer who lived at Chaddock Hall. From about 1760 Thomas Smith [or his son Thomas Smith Jnr.] employed people in a building near the windmill to card raw cotton, that is to prepare it for the hand spinners. The Smiths progressed to installing hand-operated carding machinery, and with the introduction of Arkwright’s powered carding engine in 1775 became mechanised. Buckley (1878) relates how Smith “erected a small place, near Cow Brow (Coupe Brow, now the part of Mosley Common Road south of the A580)) in which to card cotton”. This was worked by a horse-gin, where a horse walked round a circle turning a crank which was geared to the shafts and belts in the tiny mill. The report says, “it had to yield to improvements that were being brought about, but in those days it answered the purpose for which it was intended”.

Organised textile working here can be positively traced back to 1788. In that year Lewis’s Manchester Directory notes Thomas Smith, of Mosley Common, as a fustian manufacturer. [This probably refers to Thomas Smith Jnr., who lived at New House, Mosley Common, which he leased from the Warrington Grammar School.] The produce of the gin-powered mill was put out to hand spinners and weavers. Thomas [Junior?] moved further up the chain of operations by purchasing a warehouse in Lever’s Row, Manchester, and forming a partnership with Smith, Cooke and Smith as merchants to dispose of the products of the mill and outworkers. This warehouse is mentioned in his will of 1790 and land tax records of 1799.

Thomas Smith Jnr. also began a partnership with a Worsley man, Thomas Ingle, tenant of land near to what was to become St Mark’s church. His name is commemorated in the name Ingle’s Pit, a shaft to the underground canal. The venture of Smith and Ingle was a paper mill situated on the Stretford bank of the River Irwell at Throstles’ Nest, later part of Manchester Docks. Operated very successfully, it passed to Thomas’s sons, Richard and Thomas. Another of Thomas’s sons, Robert, received the Boothstown and textile interests upon the death of Thomas Smith Jnr. in 1793 [he pre-deceased his father, who died in 1808 – contrast with JBS’s notes below, and clarify.].

With advancing technology, the gin-powered mill became obsolete, and was replaced by Robert Smith in 1812 on the same site. Buckley records, “R. Smith erecting a cotton mill in the Delph where they carded and spun cotton. This he carried on for a number of years. The mill was worked by an engine and turned out to be a great advantage to the inhabitants of that part of town in finding employment for them near their homes”. This venture became known as the Delph Cotton Mill, and was the third such mill built by the Smith family in the Delph (after the original building and the building with the horse-gin).

Poor rate books of 1840 for the township of Tyldesley-with-Shakerley show £386-8s-4d as the gross estimated rental value of the mills etc owned by R. Smith. They record “a windmill, corn mill, old cotton mill, new cotton mill, warehouse, shop, sowplace [where the yarn was coated in boiling size], taking-in room [for putting warp thread on the loom beam], power loom shop, gas works, 12hp and 22hp engine and boiler houses”.

By the 1856 rates valuation of the Delph Mill, it is owned by R. Smith, but occupied by Messrs. Entwistleand Monks, and comprises only “weaving shed, warehouse, winding room, beaming room, gas works, boiler house, and 16hp engine house”. The partnership dissolved in 1866 when Mr Monks remained at Delph Mill, forming a partnership with Thomas Silcock to spin and weave jute into sackcloth, and also manufacture sacks and bags. Silcock, a member of the first Tyldesley Local Board in 1863, became sole owner of the Delph Mill in 1870, but ceased jute manufacture in 1875.

Delph Mill was let to Messrs Walsh and MacDonald, cotton manufacturers or weavers, until 1878, from when it remained empty and slowly decaying until it was demolished in 1893. The site became part of the food canning plant established by Ungers, or Allied Canners (Boothstown) Ltd, in 1943 under the name The Garden Canneries.

Stirrup Brook Mills (east of the brook), including Yates’s Mill

These mills were founded by Robert Smith, well before his father’s death. Exactly when they were established is uncertain, and it is quite possible that they were an ‘Arkwright’ mill, using his water frames to spin cotton. The ‘broken down weir’ noted by the Victorian ramblers may be a survivor from this period.

What is certain is that in 1793 Robert Smith, in partnership with Thomas Barrett of Worsley, insured his cotton mill at Stirrup Brook with the Royal Exchange Company. The risks were for £300 to cover “their cotton mill and steam engine adjoining, brick built and slated, situate at Stirrup Brook in the Parish of Worsley, under the first class of cotton risks”. A further £900 risk covered “utensils and Trade in trust and on commission including the going gears therein”. All this for a premium of £3-13s-6d. By Michaelmas (September) 1795 risks had been put down as the mill building £260, stock in trade £38, steam engine £100, and the internal machinery and gearing quaintly described as “clockmakers work therein” valued at £502 and with a premium increased to £4-16s-0d.

By the 1840s, when Robert controlled the mills on both sides of the brook, it seems that the Worsley Stirrup Brook mill carded and spun, while the Tyldesley Delph mills wove cloth and warehoused it. Some indication of the scale of industrialisation of what was still essentially a small village is shown in the 1841 census of just the Worsley side of the brook. This shows 250 persons engaged in textile working. Of these 30 are cotton weavers, 19 are power loom weavers, while 168 are simply described as working in a cotton factory. Enough are classified as spinners to confirm that the mill was an integrated process operation. (And those workers who lived on the west – Tyldesley – side of the brook are not included in these figures, being on the Tyldesley census returns.)

In the 1851 census only 107 cotton operatives are recorded on the Worsley side of the brook, although 48 were power loom weavers. Worsley township continued to levy a Poor Rate on the property, charging for factory, land, reservoir and power until 1856. At this date the elderly Smiths sold up their interests, and the first Stirrup Brook mill was demolished.

In 1862, during the American Civil War cotton famine, Charles Entwistle (who had leased Delph Mill) purchased the Worsley part of the Smith estate, including the remains of Stirrup Brook mill and the existing factory cottages. By 1866 he had rebuilt the mill on the same foundations and was in business as a cotton spinner and manufacturer. He had carding machinery and 9,000 throstle frame spinning spindles in a three-storey building alongside the brook, and 240 looms in a weaving shed alongside Chaddock Lane. He had to sell the business in 1874.

It was purchased as a going concern by the Yates family, who had begun their textile working in partnership with Peel’s of Bury. Yates’s firm was established in 1795 by John Yates. Remaining family-owned, the firm was called William Yates and Sons by 1870. William Yates Snr. died in 1898, aged 86.

William Yates had also operated as a putter-out to handworkers and had been a partner with Mr Bowers in a weaving mill in Swinton and sole owner of a Rochdale mill. Constituted as William Yates & Son, the firm continued to operate the same machinery as Entwistle until 1899, when spinning ceased and the weaving operation was extended. Further major changes came in 1910 when the old Lancashire looms were scrapped, and 320 of the automatic shuttle-changing American Northrop looms were installed.

During the second world war, Yates’s Mill made officer shirting material, and pyjama cloth for the South African navy. In 1946 there was major redevelopment. All machinery was converted to electric drive, the mill lodge was filled, and the brook culverted as a massive new weaving shed was erected. When fully equipped the mill held 460 of the Northrop automatic looms.

By the 1950s the mill was one of the most modern in the country. But despite Yates’s having a good reputation for cloth, and as employers, company reorganisation led to the closure of Yates’s mill in Boothstown in 1968.

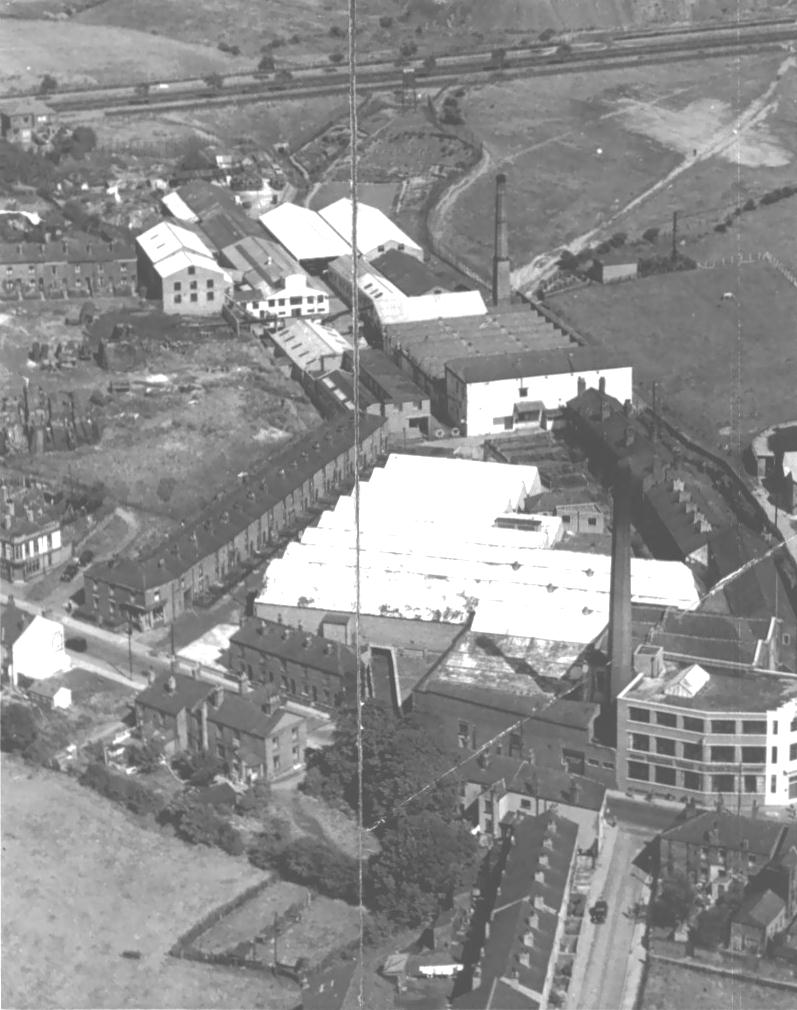

The mill (pictured above) was purchased by a furniture company and housed a discount warehouse under the name Queensway Furniture until it was demolished in the 1980s.

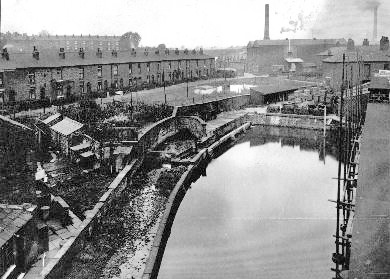

The photograph below shows Stirrup Brook alongside the reservoir at Yates’s Mill sometime after 1945. The row of cottages seen above and left of the brook is Orchard Street and has now been demolished except for the properties on the main road (Chaddock Lane). The brook is now covered by a culvert beneath a road called Border Brook Lane. The whole scene has been replaced with new housing and is now unrecognisable from this picture.

Garden Mill

James MacDonald had been a partner in business in the Delph Mill from 1875, and three years later, in 1878, opened his own premises, the Garden Mill on the opposite bank (the east side) of Stirrup Brook. Its opening ceremony included a tea party for the 100 employees transferred, and the naming of the engine ‘Faith’ by breaking a bottle of champagne. The firm was to manufacture cotton cords on 240 looms. They later also included many dobby looms capable of using up to four different shuttles in a pattern. James MacDonald lived at Meadowbank in the village.

Edward Makin & Co, of Radcliffe bought the mill in 1887, and celebrated their opening by treating their 60 Boothstown employees to a visit by barge to the Queen’s Golden Jubilee exhibition in Manchester. Capacity in the mill gradually increased until their 1897 trade directory entry showed 300 looms for regattas, stripes, gingham and fancy cloths. They closed in 1904.

Almost exactly one year later a new owner took possession of the Garden Mill. The Farnworth Journal has details in June 1905 relating to the new firm styled the Boothstown Manufacturing Company. Its article reports that, “A few well known residents of Walkden and Boothstown have floated a company to take over the weaving mill formerly of E. Makin which has been shut a year”. Its directors are listed as Dr. Lowe JP, and Messrs. W. Hartley, A. Shepherd, H. Heylin and J. Mather. The newspaper finishes with a progress report that “there are 300 looms for the manufacture of coloured goods and improvements including a new Musgrave boiler and fuel economisers. The shares are largely taken up. The looms are expected to be running in 6 to 8 weeks and to employ 100 people”.

This firm was so successful that extra capacity had to be rented in a Walkden mill. Their main customer was termed ‘the West Africa trade’, in that 90% of production was in the light, bright cottons exported to Cameroon. This continued through the first world war, and the firm was busy in the Africa trade up to the outbreak of the second world war. With the collapse of domestic trade and the extinction of exports, Garden Mill closed as a weaving concern in late 1939.

Wartime necessities brought new business. A Manchester company, Maurice Lee Ungar Ltd, had secured contracts for food supplies to the armed forces, and expanded into Garden Mill as a canning factory. After the war the firm became part of Allied Canners and the site was known as The Garden Canneries. They expanded to include the site of the old Delph Mill, and had a large advertisement clock tower on the verge of the East Lancashire Road alongside the works. The cannery closed in 1962; its buildings were subsequently demolished, and today there is housing on the site.

Mosley Common Mill

Richard Worthington appears as a “manufacturer of dimities and quilting” in a directory of 1816 that covered Tyldesley. Worthington, like the Smiths and the Yates family, was a putter-out of materials to home-based workers. He had a Manchester office, and a warehouse at 7 Bailey’s Court, Market Place. He had sufficient capital to build and equip a power loom weaving shed at Mosley Common in 1831 on land opposite the King William inn.

Worthington’s mill was first equipped with 60 pairs of looms and was later extended to hold 100 pairs. The census of 1851 details the Worthington family and their employees. Richard was then aged 73, his son Roger managed the firm, which is noted as employing 7 men, 21 women, 4 boys and 4 girls. Richard died in 1861, and Roger retired in 1871.

It appears that both the mill and their residence, Mosley House*, were sold as a job lot to James Cooke. The Tyldesley rate records show Cooke as owner-occupier of both in the following year. Textile industry directories confirm that James Cook maintained the complement of 200 looms manufacturing stripes, dimities and motties. Cooke ceased manufacture in 1881, and the mill is listed as empty for some years. It is shown on the Ordnance Survey map of 1893 and is known to have been in use as a soap factory owned by Mr Appleby in 1894. It had been demolished by 1928, the mill lodge remaining.

[* Note: 1881 census shows James Cooke at 120 Commonside, Mosley Common – his house was named Mosley Villas. He was described as a cotton manufacturer employing about 160 persons, but there was a note that the mill was ‘temporarily closed’. Next door to Cooke, a Mr Edmonds (warehouseman) lived at 122 Commonside – this house was called Mosley House.]

Parr Bridge Mill

Richard Farnworth of Tyldesley erected a weaving shed of 150 looms at in 1859 at Parr Bridge, also known as Honksford Bridge, Mosley Common. His steam plant used water from the Moss Brook alongside the mill. he is reputed to have manufactured ‘fancy work’, likely to have been striped weaves using ‘dobby’ looms – an early form of programmable machine. Richard Farnworth retired in 1865, leaving the mill empty for a short while. It then became home to a number of short-term tenants.

These included John Jackson, from 1869; Jones & Co. from 1872; and Wm. Porritt & Co. in 1876. Then its purchase by Samuel Middleton and Joseph Hewitt brought a period of stability. Middleton lived in a house next to the mill, and also ran a transport business. Hewitt lived at Oak Lea on Chaddock Lane, now the presbytery of the Holy Family RC church. They manufactured stripes, checks, havards and jeans. At an unknown date, around 1900, ownership transferred to the Forsyth Bros. before closure for some years.

The mill was bought in 1920 by a Bolton firm, Robert Farnworth (no relation to Richard), based at Ocean Mill, Settle Street, Bolton. They also had weaving sheds at Bentrick Street in Farnworth and later at the Grecian Mill in Walkden. Beginning as cotton weavers, the firm changed to weaving synthetic fibres, particularly rayon. Rayon weaving ceased at all of the firm’s mills in 1958, but their sheds continued to manufacture furnishing fabrics on dobby and jacquard looms. All production ceased at Parr Bridge in 1984, and the mill subsequently became an engineering works.

Notes on the Family of Thomas Smith

Thomas Smith was a corn dealer, who built a mill in Boothstown for grinding corn. He lived at Chaddock Hall (leasing the residence) and died there in 1793. He is also likely to have been responsible for the first mechanised cotton mill in the village, possibly where the Delph mill later stood, in around 1760. Here cotton was carded using machinery driven by a horse-gin.

His son, another Thomas Smith, in 1799 was assessed for Land Tax on a warehouse in Lever’s Row, Manchester, occupied by Smith, Cooke and Smith. It is likely that the product of the Boothstown mill was sold from there. The younger Thomas Smith lived at New House, off Coupe’s Brow (now Mosley Common Road, south of the East Lancashire Road), and died intestate in 1808, leaving £25,000. He was the father of Henry, John, Thomas, Robert and Richard, who also had interests in cotton and paper mills. Their sister Esther married Richard Ormerod, a cotton manufacturer, possibly from Leigh; she had two sisters, Ellen and Anne, and another brother, James.

Henry Smith (who lived at Hope Farm) is mentioned in Baines Gazetteer 1825 (Manchester trade directory) as Cotton Spinner of Boothstown, and family wills also indicate an interest in paper manufacture. Henry left Boothstown around 1849 and died in Manchester in 1857. Hope Farm was occupied by his brother, John, after his departure. Henry’s children continued his business interests and established commercial links between Boothstown and South America: Henry Jnr. emigrated to Montevideo, where he originally imported Boothstown cloth, and a granddaughter, Polly, moved to Buenos Aires. Henry’s other son, Johnson Parker Smith was involved in trade between Manchester and South America from the 1860s to the 1880s and was a frequent visitor to his relatives on that continent, where descendants of these Boothstown Smiths live today.

Robert Smith (1781-1863) was a paper manufacturer who was living at Chaddock Hall by 1796, where the family remained until they moved to Hope House around 1850. Robert, his sister Anne, and probably his nieces Mary and Betsy seem to be the people of those names mentioned in Mrs. Whistler’s diary. It is not known whether Mary’s interest in the “rightful and youthful incumbent” of St. Mark’s was reciprocated, but Betsy later married Rev. Thomas Morley, Curate of Ellenbrook. Robert and brother John were partners in Smith and Ingle at a place called Throstle Nest Mills, on the Stretford side of the River Irwell. They were both included in trade directories in the 1820s and 1860s.

Richard and Thomas rented the land known as Great or Farther Knathole Croft on the east side of Stirrup Brook in Boothstown and built a spinning mill there. By 1818 the firm was known as Robert Smith and Brothers. Around 1812 Thomas built the Delph mill on the eastern side of Stirrup Brook, with a coal-fired steam engine. In 1826 it was enlarged to include a shed containing 200 looms, and the firm employed some 400 workers. Baines’ Lancashire gazetteer (1825) lists the firm as cotton spinners and manufacturers, grocers and corn millers. Their Manchester address is the back of 6, Piccadilly.

An 1838 valuation refers to Robert Smith and Brothers as the owners. At that time there was a windmill, corn mill, old cotton mill, new cotton mill, warehouse, shop, sowplace, taking-in room, power loom shop, gas works, engine house and boiler house, all assessed at £322. By 1847 the firm had divided: Thomas had the old windmill, and Robert the cotton mill and lodge.

A Philip Manley was owner some time before 1869, followed by Thomas Silcock in 1871, who made jute, bags and sackings. He built a row of cottages called Silcock’s Row (this later became known as Windmill Street, then Mill Street). The Delph mills were disused by 1893, though the original building at the end of the Mill Street terrace was used a part of the later food canning factory.

Acknowledgements and Notes

This web page was compiled by Tony Smith. The stories of the seven cotton mills were provided by Glen Atkinson. The map showing the location of the sites of the mills was provided by Glen who also kindly supplied information about the windmill and the windpump at the sewage farm.

Notes in the section relating to the Smith family were taken from the family history of Judy Barradell-Smith and John Lunn’s History of Tyldesley (1953), with additional information supplied by Mrs. C.E. Mullineux. There are a few queries about Thomas Smith Snr and Thomas Smith Jnr to resolve – these are [in brackets] above.

Other original notes on this page were provided by C. Elsie Mullineux. Photographs kindly supplied by Walkden Library.